■To save children who are isolated in the classroom

At the YSC Global School, there are children from the Philippines, China, Nepal, Peru, and other countries.

At the YSC Global School, there are children from the Philippines, China, Nepal, Peru, and other countries.Let me introduce myself. I am Iki Tanaka of the Youth Support Center, an NPO corporation. I run the YSC Global School, which is situated in Fussa, Tokyo, and conducts courses in specialized Japanese for immigrant children or children who have roots abroad.

At public schools throughout the country, there are more than 37,000 children who do not speak Japanese. (as of 2014, according to Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology data). This is because, for example, they were abroad in their infancy and do not speak Japanese with their family members. During lessons they just sit around and have difficulty making friends. Among the children who need training in Japanese, about 7,000 do not receive guidance owing to a labor shortage. These are so-called “language refugee” children.

We have been offering training in Japanese for such children who have roots abroad and supported more than 400 children from 18 countries in preparing to go to a higher-level school.

The support program for parents who have refrained from applying for admission into an elementary school also covers foreigners whose applications for refugee status are pending.

The support program for parents who have refrained from applying for admission into an elementary school also covers foreigners whose applications for refugee status are pending.In particular, parents in straitened circumstances for workplace or family reasons have no choice but to send their children to public schools in Japan. In addition, there are cases such as foreign mothers who have divorced their Japanese husbands and are welfare recipients. We have been providing an environment where courses in specialized Japanese can be attended free of charge so that children from such families may receive training in Japanese without anxiety.

However, it is not only children that are targeted. Courses are also open for foreign parents, where they can learn simple Japanese necessary to communicate with school teachers and learn about customs.

■The motive goes back to my high school days living by myself in the Philippines. I had a warm feeling whenever I was spoken to.

I, who had suffered bullying throughout my days at elementary and junior high school, enrolled in a public school in the Philippines to study by myself at the age of 16 on the advice of my father. What supported me, living in the Philippine countryside as the only “foreigner,” with no knowledge of the language or the culture, was the kindness and warmth of the local people. It went so far that, when I just made a step outside, every stranger greeted me, and I could lead a carefree life there.

It all started after my return to Japan, when I met a junior high school student who had roots in the Philippines. Although she was transferred into a junior high school as soon as she came to Japan, she could not speak Japanese and so fell into truancy.

I was shocked at the present situation of children who live in Japan and have roots abroad when I first caught a glimpse of it. I thought that a child who comes from the Philippines, a country full of such warmth and kindness, and is plunged into such a cold environment in Japan, must feel extremely lonely. Moreover, I felt that there might be more children like her.

So thinking, within that year I quickly started an educational project offering training in Japanese tailored for children with roots abroad, The project became the starting point for the “YSC Global School” I run at present, which was capable of supporting more than 400 children.

■”If you lose your language, you lose yourself” The social problem we are facing

There is also a special program to support academic learning for children who have refrained from taking examinations to try and enter senior high school.

There is also a special program to support academic learning for children who have refrained from taking examinations to try and enter senior high school.At the same time, the opportunities for such children with insufficient Japanese language skills to receive appropriate training in Japanese vary greatly from region to region. Even if they receive some support at the school, it is often the case that the people in charge have no knowledge relating to training in Japanese for children, or they can receive such support for only a very limited time.

Last year, we started an initiative to support children all over the country not only through training in Japanese in the classroom but via online courses as well. The thinking behind it was a desire to reduce the number of “language refugees,” even if just by a little bit.

Not infrequently, if children grow up in an environment where they lose the ability to speak and are alone because they cannot even communicate freely, they will lose themselves. Owing to the fact that they have not received training in specialized language, even if they will be able to carry on a conversation, they will be unable to follow a deep train of thought so as to understand their interlocutors and their own inner selves. Not being able to establish their identity, they will drop out of society.

The fact that such children and young people tend to become reclusive and turn to violence will pose a heightened risk to Japanese society.

At present, the number of foreigners working in Japan is rapidly increasing. Judging only by the number of registrations, last year their number exceeded one million for the first time, and by 2020 it is expected to rise even further. I believe that from now on, in view of a situation like this, preparing a scheme of appropriate educational support for children with roots abroad becomes a very important task.

■The Japanese language classroom as a place for children where they belong

“In the past, I believed that friends were very important. But now they are all far away. I did not give in, either. I also would like to play with others. But, really, being on my own feels lonely and humiliating.”

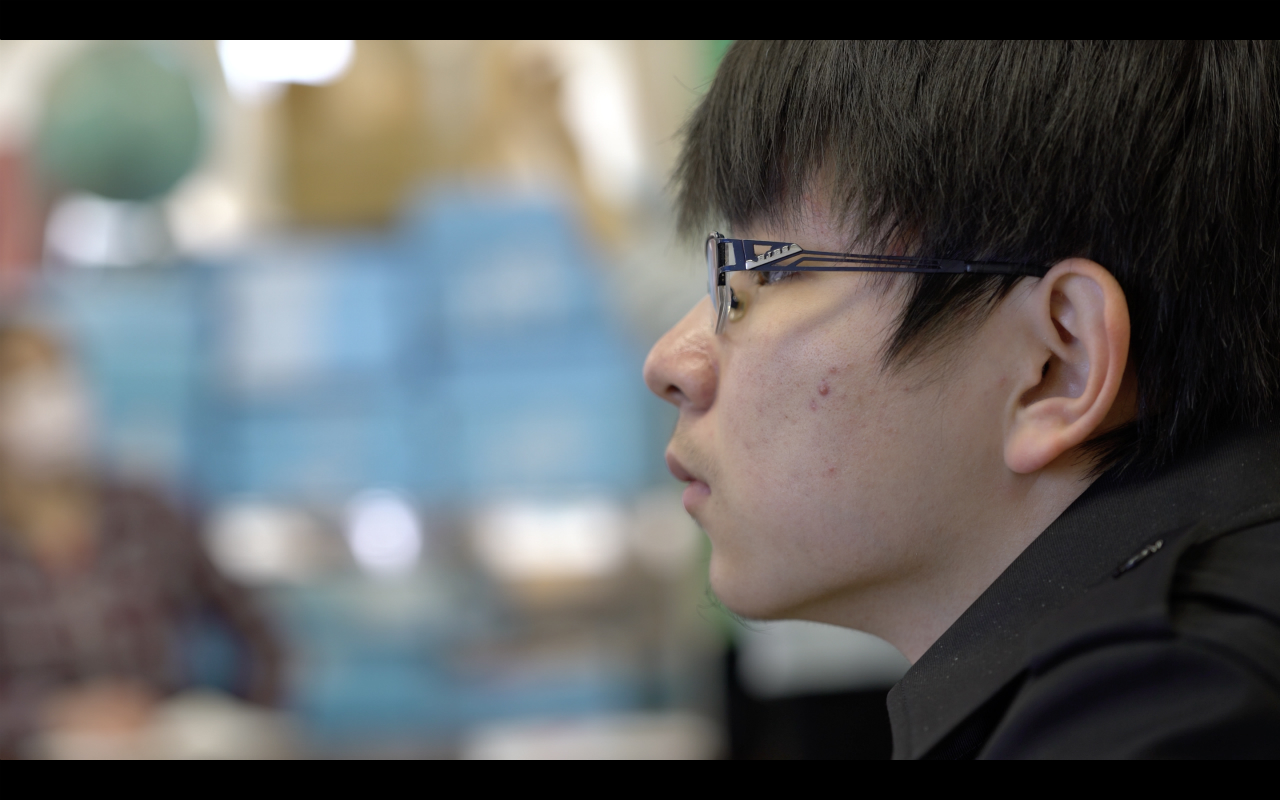

These are the words of Mr. Zou Fong (aged 16), who came to Japan from Jilin province, China, last May. He has started attending our schoolroom in order to try and take examinations to enter senior high school.

His father had come to Japan in order to work at a Chinese restaurant in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, bringing his family with him. At the time, Mr. Fong could barely speak Japanese. His dream for the future is to become a train driver with a railroad company. Going on to senior high school is indispensable for this dream to come true. Mr. Fong, while attending a municipal evening junior high school in Hachioji, has combined it with learning Japanese at our classroom. He learns not only vocabulary and grammar: we teach Japanese customs and culture, nature, history, and the like, necessary to properly use the subtle nuances of Japanese.

Mr. Fong, who could not make friends and whose loneliness was exacerbated, occasionally even wrote about his bitter feelings at SNS, in the hope of it becoming a moral support through comments added to his messages, and it supported his examinations.

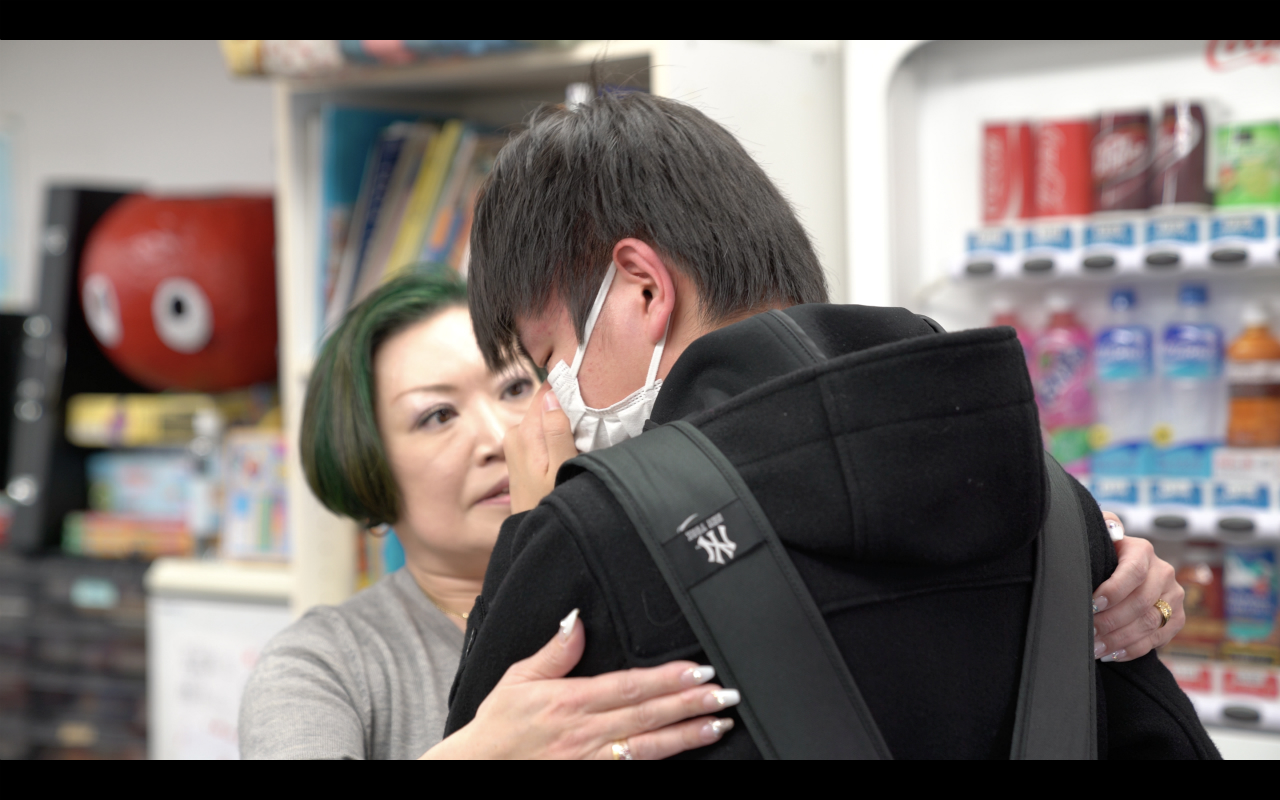

The day before the announcement of successful examinees, the lecturers embraced Mr. Fong, who was weeping from feeling the pressure, encouraged him by patting him on the back, and sent him out of the classroom. I would like the classrooms here to function as favorite places for children who go through uneasy days. It is a thought shared by the entire staff.

In the classroom, such exchange goes on between the lecturers and students. In order to support lonely children throughout the country, last year we also began an experimental rollout of an online learning system. This year, we have decided to broaden the free-of-charge scheme again, in order to expand support for children who cannot go to school for economic reasons. We also plan to reintroduce the transportation service that was temporarily discontinued for budgetary reasons.

The period during which a student becomes able to speak Japanese and able to lead a school life independently is about one year. With support for junior high school students who have refrained from taking examinations to try and enter senior high school, ¥200,000 per person will be enough to cover all the costs. Every year, among the 100 or so children we support, about 25% live in destitute households or foreigner single-parent households. This year, for such children, with a plan to secure a free-of-charge scheme for at least 20–25 students, we have started sending out messages with a view to raising ¥3,000,000 for the purpose.

We ardently hope that many people’s attention will be drawn to this problem, which tends to be overlooked by society, and continuous support will be provided. Please help us any way you can!

■ How the support money are to be spent

The funds that are required for this project will be allocated to the funds for offering the program listed below, already being offered by the corporation for a charge, free of charge to children from foreigner single-parent families and destitute households.

- A program of training in elementary Japanese

90 hours × 6 persons = ¥252,000

This is a full-time program where specialists in training in Japanese for children give instruction in basic Japanese grammar, the spoken language, and so on. - A program of training in elementary and intermediate Japanese

90 hours × 6 persons = ¥252,000

This is a full-time program for children who have completed the elementary program or have comparable skills in Japanese. - A program for 15-year-olds and older preparing to go on to senior high school

90 hours × 10 months × 5 persons = ¥1,500,000

This is a full-time program for preparing students who have come back to Japan at the age of 15 or older and who hope to go on to a municipal senior high school to take entrance examinations in Japanese. - An after-school program for preparing to go on to senior high school

45 hours × 10 months × 5 persons = ¥1,000,000

This is a full-time program to provide after-school educational support principally for students who are enrolled in a junior high school and hope to go on to a metropolitan senior high school on a full-time basis.